Who Owns Your Face?

Biometric Personality in an era of Facial Recognition Systems, Artificial Intelligence and Speech Recognition Systems

By Gordon Finlayson

Facial features are essential to human identity, our unique set of facial features are the means with which we can instantly identify one another out of the billions of humans alive on the planet. Faces are essential to your understanding of your own identity and the manner in which you understand and recognize the identities of others.

The question “who owns your face?” is not about physical ownership and possession, rather a question of what control an individual has, or should seek to have, over the use, commercial exploitation, recording, storage and processing of their facial features and other identifiable biometric characteristics such as voice prints, height, weight, blood pressure, DNA, voice prints and recordings, fingerprints and iris scans and geolocation all together comprise biometric data that can be understood as their Biometric Personality (BP).

Recent, rapid technological advances in facial recognition systems (FRS), speech recognition systems (SRS), health apps and DNA evidence have raised pressing questions about how, where and when your BP can be used by industry, governments and other individuals. FRS has transformed the way we connect with others on social media, yet by building up huge data bases of facial features and social connections technology companies are provided with an extraordinary insight into our lives and the use of FRS by law enforcement or government is being questioned for its impact on civil liberties.

“Proponents anticipate that it will unmask criminals, end human trafficking and make our world a far safer place. Critics fear that it will enable oppressive government surveillance, turn our everyday activities in to fodder for marketers, and chill free speech and expression.”[1]

Recent innovations with SRS and AI have seen the widespread deployment of SRS is homes throughout the world with products such as Amazon’s Alexa speaker and Apple’s Siri personal assistant software, yet use of these products has given technology companies unprecedented access to highly sensitive and personal sound recordings in the homes of users.

Much of your biometric identity is unique to you and yet can be captured, stored and used without your knowledge or consent and/or utilized in a manner that is outside of your expectations.

Advances in augmented reality and real time digital effects have also raised concerns over the potential misuse of BP by individuals for fraud, harassment or disinformation. The rapid development of DeepFake and digital facial reenactment (DFR) videos have shown the potential for BP to be misused to create realistic impersonations of individuals for pornography, fake news or identity theft.

Fueled by artificial intelligence, digital impersonation is on the rise. Machine-learning algorithms (often neural networks) combined with facial-mapping software enable the cheap and easy fabrication of content that hijacks one’s identity—voice, face, body. DeepFake technology inserts individuals’ faces into videos without their permission. The result is “believable videos of people doing and saying things they never did.” [2]

The existing framework for the regulation BP is a patchwork of laws, some which have evolved over centuries in the context of intellectual property, privacy or fraud and counterfeiting, with the addition of more recent laws passed in order to support the online economy, databases and cloud computing such as data protection laws or criminal laws outlawing odious practices like phishing, online fraud, revenge porn or harassment.

The law as it applies to biometric personality subsists in a number of key areas: Data Protection; Privacy; Rights of Personality; Intellectual Property (including Copyright and Trademarks); and Criminal Laws (such as those outlawing fraud, counterfeiting, phishing and revenge porn).

Facial features and voices are by nature on public display for most persons, meaning that there are substantial opportunities for aspects of BP to be collected and used without specific or informed consent.

FRS, SRS and fingerprint security have many practical benefits for both individuals and industry, however regulation of these aspects of BP are currently subject to laws that are often ill suited or exist within the grey zone of consumer agreements and shrink wrapped software licenses.

FRS

Over the past decade Facial Recognition Systems have become ubiquitous for consumers in public through their application in social media and photo sharing sites while they have simultaneously become increasingly common in law enforcement and intelligence services.

FRS can link an image of the face not only to a specific name but to the whole available personal information which is present on the social networks site profile… FRS might navigate in real time across these already available data, with the aim to match this pre-available images with the persons through the on-line facilities without the person consent or even knowledge. [3]

Across social media, FRS has become the backbone of platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Google Photos in order to establish relationships and connections through photographs. As social media data sets have expanded and the speed of processing for FRS has reduced.

The potential of FRS has changed the landscape radically in recent years as a result of the development of the software and the increasing availability of connected video enabled devices such as mobile phones and proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT).

The roll out of FRS technology into more areas of public and private life is raising concerns amongst legal scholars and privacy advocates. Law professor Woodrow Hartzog and ethics scholar Evan Selinger, have singled out FRS technology as being so dangerous that nothing less than a total ban would be acceptable.[4]

But we believe facial recognition technology is the most uniquely dangerous surveillance mechanism ever invented. It’s the missing piece in an already dangerous surveillance infrastructure, built because that infrastructure benefits both the government and private sectors. And when technologies become so dangerous, and the harm-to-benefit ratio becomes so imbalanced, categorical bans are worth considering.

The President of Microsoft, Brad Smith recently called for further discussion and government regulation of this field, recognizing the tremendous changes afoot as a result of this technology.

“So, what is changing now? In part it’s the ability of computer vision to get better and faster in recognizing people’s faces. In part this improvement reflects better cameras, sensors and machine learning capabilities. It also reflects the advent of larger and larger datasets as more images of people are stored online. This improvement also reflects the ability to use the cloud to connect all this data and facial recognition technology with live cameras that capture images of people’s faces and seek to identify them – in more places and in real time”. [5]

Evidence of the changing landscape for FRS can be seen in the disruptive Russian social media system, FindFace, which offers a service that allows for the public to identify individuals from their photographs based on data derived from social media accounts. FindFace has demonstrated the increasing relevance of FRS as a real time solution as a result of the speed with which its algorithms search large data sets with the use of only limited processing power. The founder of FindFace, speaking to the Guardian, Alexander Kabakov, notes that the technology being used on the platform is transformative.

“Three million searches in a database of nearly 1 billion photographs: that’s hundreds of trillions of comparisons, and all on four normal servers. With this algorithm, you can search through a billion photographs in less than a second from a normal computer.”[6]

FRS become an essential tool in law enforcement, with a recent analysis of FRS finding that as many as half of the US population has their facial identity stored in law enforcement systems. According to the Atlantic, FRS is already used by police departments in half of all US states, exposing around 117 million Americans to FRS systems.

“Police departments in nearly half of U.S. states can use facial-recognition software to compare surveillance images with databases of ID photos or mugshots. Some departments only use facial-recognition to confirm the identity of a suspect who’s been detained; others continuously analyze footage from surveillance cameras to determine exactly who is walking by at any particular moment. Altogether, more than 117 million American adults are subject to face-scanning systems.”[7]

The growing prevalence of FRS has become an issue of major concern for civil rights organizations as FRS is adopted by smart phone manufacturers, banks for verification purposes and commercial stores to monitor consumption habits.[8]

A tipping point in the debate came recently following a Trump government announcement that it would deploy FRS to identify undocumented migrants in the US, a move that resulted in the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) calling for Amazon, a leading retailer of FRS technology to cease selling its technology to the Federal Government.

“The ACLU, along with nearly 70 other civil rights organizations, has asked Amazon to stop selling facial recognition technology to the government and further called on Congress to enact a moratorium on government uses of facial recognition technology”.[9]

In Europe, UK civil liberties body, Liberty, has highlighted the dangers of facial recognition technology, noting that facial recognition software lacks regulation unlike other biometric data such as fingerprints and DNA, and insufficient debate has occurred around the potential use of the technology. Further, Liberty highlighted that analysis of the London Metropolitan Police’s trails found that the current technology is 98% inaccurate.

“When we were invited to witness the Met’s trial of the technology at Notting Hill Carnival last summer, we saw a young woman being matched with a balding man on the police database. Across the Atlantic, the FBI’s facial recognition algorithm regularly misidentifies women and people of colour. This technology heralds a grave risk of injustice by misidentification, and puts each and every one of us in a perpetual police lineup.”[10]

The collection, processing and control of BP through FRS systems should be an issue of public debate and discussion, while there are very good reasons to implement FRS for law enforcement where it could save lives and reduce criminal activity, it is important that we understand the limitations of the technology in order to avoid potential reliance on such technology without appropriate oversight.

SRS

Recent incidents with Apple’s voice activated Siri application have highlighted the extraordinary access that private corporations are being given to our homes and lives when they use and store our BP, it was reported in the Guardian newspaper that Apple employees and contractors regularly listened to recordings made by Apple devices in homes around the world:

Apple contractors regularly hear confidential medical information, drug deals, and recordings of couples having sex, as part of their job providing quality control, or “grading”, the company’s Siri voice assistant, the Guardian has learned.[11]

The issues concerning Siri recordings and similar issues exposed at Amazon with its Alexa product[12] demonstrate that despite the appearance that such systems are driven by anonymous AI systems, that human intervention and review is very much an integral part of the development of such systems. Without controls to ensure that actual sound recordings are not kept of SRS systems and that employees or contractors are unable to access live or recorded data it is clear that the privacy of consumers is being jeopardized.

Further, with the collection of voice biometric data, recordings, transcripts and digital voice profiles technology companies are building up a profile of users that can easily be repurposed for DeepFake voice imitation using AI systems. If not regulated carefully and protected with effective security the biometric voice data gathered by companies such as Apple and Amazon could easily be used for BP identity theft if it fell into the wrong hands through a data breach or exploit.

The issues at Apple and Amazon, in the context of the far reaching and damaging data breaches at Facebook[13] demonstrate that in the fast moving and highly competitive technology field that the commercial interests of tech companies are not always aligned with that of consumers or the wider public.

DeepFakes and Augmented Reality

In the context of an online economy that is facing a global challenges in relation to identify fraud, online disinformation, protection of privacy and fake news the advent of DeepFake technology and AI are further undermining our ability to control or track the use of our BP.

Augmented reality (AR) is the process of using digital effects in real time to change or alter a live video feed using a mobile phone, glasses, head up display, tablet or computer. By mapping the live video feed and imposing digital effects onto it, AR allows us to directly alter our digital representation online in real time, or the perception of reality around us.

Practical examples of AR include Google Translates real time translation service, which takes a video stream from your phone or tablet and maps the image searching for characters in a foreign language, then interprets, translates the text and overlays a digital image of the text in your native language across the real-life video image.

One of the most common uses of AR is Snapchat filters, which use rudimentary DFR systems to map the faces of video messaging users and to add flowers, bunny ears or amusing masks onto the participant’s faces, while Apple’s Clips application allows users to change their environment in real time, transporting them into a cartoon New York, the set of Monsters Inc. or to Nemo’s Reef.

On social media, individuals are able to use filters or avatars to alter their appearance or background while DFR is facilitating the real time impersonation of an individual in a convincing manner[14]. Yet while these new technological developments are creating new opportunities for communication and creativity, the same tools can also be used to hijack identities for the production of DeepFake video news, pornography or for criminal fraud.

AR is not new technology. Head up displays in fighter jets that displays information about navigation, engineering or weapons systems has been around for many decades and the film industry has been pioneering special effects over decades. Yet the growth of mobile phone computing power, growing sophistication of visual effects technology, GPS, haptics and improvements in camera technology have brought AR to a point where it is effectively blurring the lines between reality and fantasy in real time.

Fueled by artificial intelligence, digital impersonation is on the rise. Machine-learning algorithms (often neural networks) combined with facial-mapping software enable the cheap and easy fabrication of content that hijacks one’s identity—voice, face, body. DeepFake technology inserts individuals’ faces into videos without their permission. The result is “believable videos of people doing and saying things they never did.” [15]

In January 2018, Motherboard, a Vice website published an article titled “We Are Truly F***ed” detailing the recent availability of a new consumer digital effects technology, one that would go on to be dubbed ‘DeepFake’ after the Redditor that first popularized the technology.

In December, Motherboard discovered a Redditor named ‘deepfakes’ quietly enjoying his hobby: Face-swapping celebrity faces onto porn performers’ bodies. He made several convincing porn videos of celebrities—including Gal Gadot, Maisie Williams, and Taylor Swift—using a machine learning algorithm, his home computer, publicly available videos, and some spare time. [16]

In the months after Motherboard identified the trend, Vice discovered that the DeepFake trend had greatly expanded in popularity, with major porn sharing sites now inundated with DeepFake pornography and widely disseminating fake celebrity pornography based on free, open access technology that can be deployed on standard desktop computers.

While DeepFake technology currently still requires a reasonable amount of computer processing power and storage in order to produce a convincing fake, the stage is already set for this kind of technology to occur in real time.

Scientists from Stanford University and the Max Plank Institute recently developed the Face2Face[17] technology which allows for the real time facial mapping of a video feed of one person to be overlaid with the facial features of another, allowing for DFR to be deployed in real time.

By using facial mapping and merging the video with that of real people, DeepFakeDeepFake, Face2Face has managed to produce credible, real time impersonations of digital identities with the use of only basic computing resources, providing for the potential in the near future that such DFR technology will have widespread adoption in society in a way similar to Snapchat filters through messaging applications or in higher resolution through video editing software.

The rapid dissemination and development of DeepFake technology over a mere matter of months highlights example of the power of a massively networked society facilitated by social media to develop new technology rapidly, organically and with a level of moral ambivalence that can potentially result in the invasion of privacy of individuals. As Robert Chesney and Danielle Citron point out, the DeepFake phenomenon has the potential to create a great deal of harm to the individuals targeted by such videos.

Although the sex scenes look realistic, they are not consensual cyber porn. Conscripting individuals (more often women) into fake porn undermines their agency, reduces them to sexual objects, engenders feeling of embarrassment and shame, and inflicts reputational harm that can devastate careers (especially for everyday people). Regrettably, cyber stalkers are sure to use fake sex videos to torment victims. [18]

Just as social media memes disseminate themselves faster than a flu virus, we now face a world where not only content, but also major technological shifts can occur rapidly, without the direct engagement of corporations, simply based on the distributed power of engaged and motivated open source programmers.

In September 2019 the first reported case of DeepFake voice identity theft was reported by an insurance company, the head of a the UK branch of a German company transferred $240,000 to a third party bank account after he received a phone call he believed to be his boss at his parent company, “The request was “rather strange,” the director noted later in an email, but the voice was so lifelike that he felt he had no choice but to comply”[19]. The tech company Symantec has stated that it is aware of more unreported cases and potential losses are already estimated in the millions. Given the sophistication of existing phishing and email fraud operations it seems likely that both DeepFake voice and video technology will soon become commonplace as a means of deception and fraud.

But the synthetic audio and AI-generated videos, known as “deepfakes,” have fueled growing anxieties over how the new technologies can erode public trust, empower criminals and make traditional communication — business deals, family phone calls, presidential campaigns — that much more vulnerable to computerized manipulation.[20]

As DeepFakes now undermine our ability to determine truth from fiction, technology experts believe that systems that can routinely identify DeepFake is some distance away. A leading expert in this area, Dartmouth professor Hany Farid, said that it could be decades before we develop technology sufficient to identify well constructed DeepFake video – something that has the potential to greatly disrupt the criminal justice system and undermine laws of evidence.

“We’re decades away from having forensic technology that … [could] conclusively tell a real from a fake. If you really want to fool the system you will start building into the DeepFake ways to break the forensic system.”. [21]

In a world where social media has given rise to a bewildering proliferation of news outlets that peddle in conspiracy theories, outright falsehoods or misrepresentations, the use of DeepFake technology at the last hour in an election to show a politician engaging in bribery, corruption, outright racism or domestic violence could have a material impact on election results.

The spread of DeepFakes will threaten to erode the trust necessary for democracy to function effectively, for two reasons. First, and most obviously, the marketplace of ideas will be injected with a particularly-dangerous form of falsehood. Second, and more subtly, the public may become more willing to disbelieve true but uncomfortable facts.[22]

We live in an era where judicious and unscrupulous use of technology has been demonstrated as an influencing factor in the outcomes of elections and referenda[23]. In the context of a market where the credibility of news reporting is regularly questioned and the dissemination of false news articles by social media is common, DeepFake video is likely to further undermine the ability of audiences to determine the accuracy of news and information.

Cognitive biases already encourage resistance to such facts, but awareness of ubiquitous DeepFake may enhance that tendency, providing a ready excuse to disregard unwelcome evidence. At a minimum, as fake videos become widespread, the public may have difficulty believing what their eyes (or ears) are telling them—even when the information is quite real. [24]

The mass collection, storage and processing of BP has other implications for technology, society and industry. The ready ability of individuals and companies to easily capture BP such as facial features and voice prints combined with advances in real time digital effects, real time facial replacement, DeepFakes and augmented reality is redefining our perception of reality itself.

Together the legal and regulation of FRS – the rights of individuals concerning the collection, representation, manipulation, processing, storage, usage, ownership and interpretation of facial features and associated aspects of physical personal identity.

The regulation of BP has far reaching implications for society and the manner in which we as individuals interact and engage with technology, the manner in which law enforcement and intelligence services enforce laws in society and the means by which corporations engage and track our consumer patterns.

The rapid pace of change of technology in the areas of FRS, Augmented Reality, AI and Big Data have leapfrogged legal regulation and jurisprudence on the rights of personality, traditional intellectual property laws, media regulations, criminal laws and data protection regimes. The commercial basis of laws of personality or disclosure and consent structures of data protection laws are often insufficient to address the widespread use of FRS and the proliferation of Augmented Reality, while media regulations and criminal laws are insufficient to regulate the potential risks associated with the production of DeepFake videos or the potential for real time identity theft through DFR.

Data Protection

When considering the regulation of biometric personality, data protection laws are one key way in which consumers can exert control over the use of their personal image. Data Protection laws ere first enacted in response to the growth in database technology and since the advent of the Internet have been greatly expanded in order to regulate and manage the manner in which a wide variety of PI can be stored, controlled and processed. Data Protection laws are structured to protect what is usually defined as personal data (PD) or personal information (PI),

Biometric Personality has unique characteristics that separate it from the general category of what the data protection laws generally understands as Personal Information (PI), while BP comprises a subset of PI in many circumstances BP has unique characteristics due to the often public nature of BP like facial features or voice prints.

PI includes a wide variety of data that constitute specific information that can identify or be linked to an individual such as phone numbers, address details, social security numbers and financial or health records. While BP also usually is defined as PI, it on the other hand comprises metadata such as voice, face or finger prints, voice recordings, video recordings or interaction and engagement with social media, voice commands or security software.

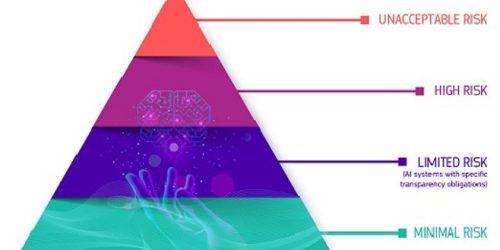

The recently enacted GDPR in the EU is the most far reaching and sophisticated attempts at regulating the use PI, yet still lacks the scope or remit to deal with all aspects of the use of , but are ill suited to dealing with the new, complex and rapidly evolving issues that relate to areas such FRS, AR, BD or the use of DeepFakes.

Some of the most complex questions about personal identity is not about how it can be bought or sold in a willing transaction by a famous actor – rather it is about all of you and how much control you really have when it comes to the digital capture and use of your face? How, where or why it is captured, stored, shared, monitored, altered and possibly commercialized by corporations, advertisers, law enforcement or social media.

Over the past decade, technology has started to replicate our innate abilities of facial recognition, using artificial intelligence systems and big data to use our faces as a security key, marketing tool or social media tool.

Facial Recognition Systems (FRS) are used effectively across photo sharing and social media platforms to identify relationships and connections while law enforcement and intelligence services worldwide now use FRS in conjunction with closed circuit systems to monitor their populations.

“…faces, unlike fingerprints, gait, or iris patterns, are central to our identity. Faces are conduits between our on- and offline lives, and they can be the thread that connects all of our real-name, anonymous, and pseudonymous activities. It’s easy to think people don’t have a strong privacy interest in faces because many of us routinely show them in public. Indeed, outside of areas where burkas are common, hiding our faces often prompts suspicion.”[26].

US jurisprudence in the 20th century helped to lay the groundwork to frame concepts of rights of personality and privacy, but Europe has lead the way in the past decades with the introduction of sophisticated data protection regulations that provide detailed and far reaching rights for consumers over their PI. In 2018, the EU introduced the General Regulation on Data Protection, currently the most sophisticated international instrument for the management of data protection in the digital age.

The GDPR carefully regulates the means on which corporations collect, process and store personal data of individuals resident in the European Union. In recognition of the global nature of Internet commerce the GDPR has extra-territorial jurisdiction, applying to both companies in the EU and any company that controls or processes the data of EU residents anywhere in the world.

The GDPR provides certain protections for consumers over the use of their BP, yet due to its focus on consumer protection there are a number of key areas in which the GDPR lacks the appropriate mechanisms to assist consumers in the enforcement of their rights, particularly with regards to the misuse of BP by the means of identity appropriation and misuse in DeepFake videos.

Although the GDPR is not entirely comprehensive in its coverage of BP, it does effectively regulate some key areas as the definition of personal information (PI) for the purpose of the GDPR is drafted very broadly and includes in its definition of biometric data such a facial features, fingerprints, DNA, iris scans and regulates the collection, storage and processing of such biometric PI by corporations.

“…a very specific cautious approach is needed in the collection of biometric data, as they can expose ‘sensitive information’ about the persons, including information about health, genetic background, age or ethnicity. Under the new EU Regulation 2016/6798 (hereinafter the GDPR), biometric data has been classed as ‘sensitive data’. Processing of biometric data is prohibited unless special requirements are fulfilled.”

Biometric data is defined under the GDPR as ‘sensitive PI’, and subject to the most stringent controls possible, however given the omnipresent use of FRS in social media and the growing use of use of voice recognition software the regulation of BP this poses significant challenges for the deployment of FRS systems in the EU. In order to collect and store PI the GDPR stipulates:

- clear and unambiguous consent for the collection, storage and processing of that PI;

- consent can be withdrawn at any time at which point the relevant organization must delete all records relating to that individual; and

- consent must be clear, intelligible, not in legal language and provide information as to the purpose that the PI will be used for.

Further, any system that obtained the appropriate consents would still be bound by the stringent guidelines for storage and usage of such data under the GDPR where all data subjects have the following rights:

- to be informed as to whether PD about them is being held, the location and the reason for the data storage;

- to be forgotten (Data Erasure) which means that PD of data subjects must be erased on request (though data controllers may weigh up whether the request is in the public interest);

- to obtain a copy of their PD free of charge in a portable electronic format which can be transferred to another controller;

- the right to restrict processing for legitimate reasons; and

- to have errors rectified where they find inaccuracies in PD held by a controller.

The manner in which FRS are deployed means that they would be almost impossible to deploy or lack any practical usage without processing sensitive personal information. As Coserau points out in an analysis of FRS under the GDPR regime, the use of FRS in commercial retail is fraugt with challenges:

In commercial retail, FRS might only collect data that will be analyzed instantly in the cloud, without actual storage of the data, and conclude outcomes before deleting the data. On the other hand, the data might be stored for further reference. In both situations, if the collected data allows for identification, the processing should be considered processing of personal data (even if the data is not stored).[27]

The GDPR seems to pose very significant challenges for the commercial deployment of widespread FRS systems in the EU, not least because of the challenges involved in obtaining clear and unambiguous consent for data collection. While such consents may be feasible to obtain in a work context for security systems, for phones or bank verification where there is a specific reason for verification, the widespread use of FRS for monitoring consumer habits in a shopping mall for example would make it almost impossible to obtain clear consent as Coserau notes:

“In consequence, on the one hand, if the information is not clear or sufficient for ‘direct identification’ the processing of images will not be considered personal data. On the other hand, if this template or the end result is linked with a pre-determined individual’s record or profile, the outcome will likely be considered personal data”. [28]

Further the rights of consumers to be forgotten, withdraw consent or to obtain digital copies of their personal data may make the administration of such systems costly and unfeasible.

Rights of Personality

The US has long accepted the right of personality as a personal property right, in Haelan Laboratories, Inc. v. Topps Chewing Gum, Inc., the Court of Appeals first expressly recognized the right of publicity as:

…a man has a right in the publicity value of his photograph, i.e., the right to grant the exclusive privilege of publishing his picture… This right might be called a “right of publicity.” For it is common knowledge that many prominent persons … would feel sorely deprived if they no longer received money for authorizing advertisements, popularizing their countenances, displayed in newspapers, magazines, busses, trains and subways. This right of publicity would usually yield them no money unless it could be made the subject of an exclusive grant which barred any other advertiser from using their pictures.’[29]

The US considers personality rights as rooted to privacy law, originally defining the right as long ago as 1890 as the “right to be left alone”. [30] Rights of Privacy were further expanded on by William Prosser in the 20th Century, defining four key Torts of Privacy as:

1) Protection against intrusion into one’s private affairs;

2) Avoidance of disclosure of one’s embarrassing private facts;

3) Protection against publicity placing one in a false light in the public eye; and

4) Remedies for appropriation, usually for commercial advantage, of one’s name or likeness. [31]

Under the scope of the laws of publicity, the use of an individual’s likeness for the purpose of augmented reality or DeepFakes could amount to an unauthorized appropriation of a likeness.

a plaintiff to prove that the information published must “must portray the plaintiff in a false or misleading light”, be “highly offensive or embarrassing to a reasonable person of ordinary sensibilities” and published “with reckless disregard as to its offensiveness”.[32]

Certainly when it comes to DeepFake pornography it would be reasonable to assume that the courts would recognize that the creation of such a video would be embarrassing to the actor and the publication would be with reckless disregard to the offensiveness to the actor or the public.

False Light is a useful action when considering DeepFake videos both for pornography and fake news as in many US states, False Light claims can address issues implications, not just false statements, the appropriate test for a claim in defamation in the US.

…untrue implications rather than directly false statements. For instance, an article about sex offenders illustrated with a stock photograph of an individual who is not, in fact, a sex offender could give rise to a false light claim, even if the article and photo caption never make the explicit false statement (i.e., identifying the person in the photo as a sex offender) that would support a defamation claim. [33]

Yet as Andrew Osorio notes, the False Light doctrine is criticized for being unnecessary due to analogous causes of action under the Torts of defamation and privacy and has a potentially chilling effect on the rights of free speech.

“…continued recognition of false light invasion of privacy may create an unwarranted chilling effect on free speech while providing little more than a source of mischief for plaintiffs who artfully pad their pleadings to intimidate defendants, bogging down courts in the process.”[34]

A DeepFake video could also be seen to be a misrepresentation of an individual’s actions, giving rise to a potential action for defamation by falsely portraying an individual as a person who would knowingly produce and distribute a pornographic video.

Yet all of the actions above are actions in Tort, actions that could be taken against a defendant that can be clearly identified, yet due to the increasing availability of the technology required to create DeepFake videos and the P2P economy means that both the creators and distributors of DeepFake videos are likely to be difficult to identify for individual plaintiffs and litigation costly and drawn out.

The damaging impact of this kind of augmented reality on reputations may require more direct intervention and criminal sanctions similar to the legislation enacted to prevent revenge porn as we will discuss later.

In the EU, the pattern of protection for personality and identity varies from member state to member state, making the issue of protection of personal rights challenging across the market. In the United Kingdom, there is no distinct right of personality, instead, common law rights in relation to defamation, trespass and advertising codes are used to protect individuals as well as trade mark rights and the connected doctrine of ‘passing off’.[35]

In France, rights of personality are linked to the wider rights of authors and moral rights, connected to ‘image rights’ which broadly includes: “the moral rights of authors; the right to privacy, the right to protect one’s honor and reputation, and the right to control the use of one’s image” [36]. In Germany, Copyright law has been extended to include a right of consent for the use of an individual’s picture, name, voice and other personal aspects.

The issues surrounding DeepFakes are an extension of the questions that are currently being grappled with concerning facial recognition technology in relation to the under the EU new data protection regime, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) where biometric data constitutes ‘sensitive information’ and is subject to the highest standard of regulation. Would it then be possible to apply data protection principles to DeepFake, either authorized or unauthorized, with their focus on rights and regulation of data, it is arguable that the GDPR is less of an appropriate mechanism to manage rights in this area than US personality rights laws.

Criminal Laws – Fraud; Revenge Porn and Misrepresentation; Press Regulation; Defamation

Recent precedent for widespread privacy issues can be seen in the adoption of criminal laws against revenge pornography, the phenomenon of ex-partners distributing pornographic videos or images to online sharing sites. The actions, generally taken by men against their female partners evoked a widespread reaction to the invasion of privacy and the reputational issues that women regularly faced as a result of such actions. Aided by unscrupulous Web site operators revenge pornography has become a major societal problem in the US.

A 2016 report from the Data & Society Research Institute and the Center for Innovative Public Health Research found that one in 25 people in the U.S. have either been victims of revenge porn or been threatened with the posting of sensitive images in their lives. That number jumps to one in 10 for young women between the ages of 15-29. And the numbers go even higher for young women who are lesbians or bisexual.[37]

The significance of the issues has prompted some legislatures to enact criminal laws to outlaw the practice of distribution of revenge porn. It seems logical that similar legislation could be enacted to tackle the problems that are going to be created as a result of the production and distribution of DeepFake videos whether that happens to be for the purposes of pornography, for the dissemination of fake news or fraud.

The precedent created in revenge pornography laws shows an interest on the part of legislatures to controlling the excesses of online activity where such legislation is designed to control excessive or widespread invasion of privacy. Federal legislation in the US recently proposed by Senator Kamala Harris, the Ending Nonconsensual Online User Graphic Harassment (ENOUGH) Act of 2017, has been backed by Facebook and Twitter and would and would amend title 18 of the United States Code, to provide:

…that it is unlawful to knowingly distribute a private, visual depiction of an individual’s intimate parts or of an individual engaging in sexually explicit conduct, with reckless disregard for the individual’s lack of consent to the distribution, and … the reasonable expectation of the individual that the depiction would remain private; and… harm that the distribution could cause to the individual; and… without an objectively reasonable belief that such distribution touches upon a matter of public concern. [38]

The ENOUGH Act provides criminal sanctions of up to 5 years in jail, which, if applied to DeepFakes would be a powerful deterrent to those who might seek to use a DeepFake to harass, embarrass or create misinformation.

While it seems possible that a court might apply such laws to DeepFake pornography given the implicit lack of consent involved, however, such laws would be unlikely to apply to DeepFake news videos or the use of DFR for fraud or deception and more sophisticated regulation is likely to be required in order to regulate such activity.

Conclusions

While privacy and data protection laws provide some of the tools required to protect individual rights and freedoms in specific jurisdictions, in the context of a world driven by big data, IoT and AI clear set of legal principles are necessary to drive forward development and implementation of technology, while respecting fundamental human rights.

Yet it is the view of many other scholars, that an outright ban on FRS is contrary to public interests in the development of technology and the positive benefits that can accrue to society as a result of its use. Brad Smith, President of Microsoft has joined calls for regulation of FRS [39] and a robust regulatory regime based on data protection principles and human oversight are necessary in order to counter the potential negative impact of issues around false attribution, errors and racial bias in FRS and the potential negative impact of DFR in areas such as DeeFake news, pornography and fraud.

It may be that the regulation of a set of principles concerning BP may be useful in developing a technology adaptive approach to issues around public identity that will be sufficient to deal with both the current challenges posed by FRS and DeepFake videos, but also the challenges posed by unimagined technology. As noted by Judith Donath, banning FRS outright will be counter-productive to the development of useful technology.

“… finding ways to protect freedom and privacy in the face of rapidly advancing surveillance and analysis technologies is important and urgent. But calling for a ban on face recognition technology is not the right approach — instead, we need to seek regulation based on the qualities and capabilities of the technology, not the technology itself. Ideally this approach would avoid an arms race of regulation-dodging technologies, and instead spur development of innovations that complied with the permitted scope of more limited surveillance.”[40]

The new opportunities for technological innovation and the development of new and novel means of communication, media and interactive environments through the use of BP is a cause for significant optimism when it comes to the adoption and use of the technologies outlined in this paper. But it is key to the development of such new technologies that the rights and freedoms enjoyed by individuals in society today should not pared back in order to simply facilitate commercial development.

It seems apparent that the new technological developments created by Big Data, AI, FRS, DFR an Augmented Reality have the potential to create a more dynamic and exciting society. Yet the potential for unscrupulous governments, individuals or corporations to use such technology to limit freedoms or infringe on the rights of privacy of individuals is perhaps more significant than it has ever been before in history. Ensuring that these new technologies will have a positive impact on society will be a subject for much discussion and work over the coming years and decades to ensure that the right balance is met between protecting individual privacy, limiting fraud, enabling rights of free speech and ensuring the development of a vibrant and innovative marketplace for new technology.

Originally published: Finlayson, Gordon, 2018, “Identity Crisis”, Entertainment, Droit, Medias, Art, Culture, 2018/6, Bruylant, pp.396-411.

[1] Judith Donath, July 23, 2018, Medium, https://medium.com/@judithd/you-are-entering-an-ephemeral-bio-allowed-data-capture-zone-5ecafd2dbdaf

[2] DeepFakes: A Looming Crisis for National Security, Democracy and Privacy? By Robert Chesney, Danielle Citron

Wednesday, February 21, 2018, 10:00 AM https://www.lawfareblog.com/deep-fakes-looming-crisis-national-security-democracy-and-privacy

[3] Coseraru, R. 2017 Facial Recognition Systems and Their Data Protection Risks Under The GDPR Master Thesis Law and Technology LL.M. Tilburg University http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=143731

[4] Woodrow Hartzog, August 2, 2018, Facial Recognition Is the Perfect Tool for Oppression https://medium.com/s/story/facial-recognition-is-the-perfect-tool-for-oppression-bc2a08f0fe66

[5] Smith, Brad, 2018, Facial recognition technology: The need for public regulation and corporate responsibility

[6] Walker, S. 17 May 2016 Face recognition app taking Russia by storm may bring end to public anonymity,

[7] Half Of American Adults Are In Police Facial-Recognition Databases Kaveh Waddell OCT 19, 2016; Https://Www.Theatlantic.Com/Technology/Archive/2016/10/Half-Of-American-Adults-Are-In-Police-Facial-Recognition-Databases/504560/

[8] Coseraru, R. 2017 Facial Recognition Systems and Their Data Protection Risks Under The GDPR Master Thesis Law and Technology LL.M. Tilburg University http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=143731

[9] https://www.aclu.org/news/aclu-comment-microsoft-call-federal-action-face-recognition-technology

[10] Spurrier, Martha, Wed 16 May 2018, Facial recognition is not just useless. In police hands, it is dangerous

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/jul/26/apple-contractors-regularly-hear-confidential-details-on-siri-recordings?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

[12] https://techcrunch.com/2019/08/09/amazons-lead-eu-data-regulator-is-asking-questions-about-alexa-privacy/

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/oct/03/facebook-data-breach-latest-fine-investigation?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

[14] Thies et al, 2016, Face2Face: Real-time Face Capture and Reenactment of RGB Videos https://web.stanford.edu/~zollhoef/papers/CVPR2016_Face2Face/paper.pdf

[15] DeepFakes: A Looming Crisis for National Security, Democracy and Privacy? By Robert Chesney, Danielle Citron

Wednesday, February 21, 2018, 10:00 AM https://www.lawfareblog.com/deep-fakes-looming-crisis-national-security-democracy-and-privacy

[16] We Are Truly Fucked: Everyone Is Making AI-Generated Fake Porn Now Samantha Cole Jan 24 2018, 10:13pm https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/bjye8a/reddit-fake-porn-app-daisy-ridley

[17] Thies et al, 2016, Face2Face: Real-time Face Capture and Reenactment of RGB Videos https://web.stanford.edu/~zollhoef/papers/CVPR2016_Face2Face/paper.pdf

[18] DeepFakes: A Looming Crisis for National Security, Democracy and Privacy? By Robert Chesney, Danielle Citron

Wednesday, February 21, 2018, 10:00 AM https://www.lawfareblog.com/deep-fakes-looming-crisis-national-security-democracy-and-privacy

[19] https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/09/04/an-artificial-intelligence-first-voice-mimicking-software-reportedly-used-major-theft/?noredirect=on

[20] https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/09/04/an-artificial-intelligence-first-voice-mimicking-software-reportedly-used-major-theft/?noredirect=on

[21] DeepFakes: A Looming Crisis for National Security, Democracy and Privacy? By Robert Chesney, Danielle Citron

Wednesday, February 21, 2018, 10:00 AM https://www.lawfareblog.com/deep-fakes-looming-crisis-national-security-democracy-and-privacy

[22] Robert Chesney, Danielle Citron, February 21, 2018 DeepFakes: A Looming Crisis for National Security, Democracy and Privacy? https://www.lawfareblog.com/deep-fakes-looming-crisis-national-security-democracy-and-privacy

[23] Emma Graham-Harrison, Vote Leave broke electoral law and British democracy is shaken 17 July 2018 https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/jul/17/vote-leave-broke-electoral-law-and-british-democracy-is-shaken

[24] Robert Chesney, Danielle Citron, February 21, 2018 DeepFakes: A Looming Crisis for National Security, Democracy and Privacy? https://www.lawfareblog.com/deep-fakes-looming-crisis-national-security-democracy-and-privacy

[25] Judith Donath, July 23, 2018, Medium, https://medium.com/@judithd/you-are-entering-an-ephemeral-bio-allowed-data-capture-zone-5ecafd2dbdaf

[26] Woodrow Hartzog, August 2, 2018, Facial Recognition Is the Perfect Tool for Oppression https://medium.com/s/story/facial-recognition-is-the-perfect-tool-for-oppression-bc2a08f0fe66

[27] Coseraru, R. 2017 Facial Recognition Systems and Their Data Protection Risks Under The GDPR Master Thesis Law and Technology LL.M. Tilburg University http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=143731

[28] Coseraru, R. 2017 Facial Recognition Systems and Their Data Protection Risks Under The GDPR Master Thesis Law and Technology LL.M. Tilburg University http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=143731

[29] Haelan Laboratories, Inc. V. Topps Chewing Gum, Inc., 202 F.2d 866 (2d Cir.), Cert. Denied, 346 U.S. 816 (1953).

[30] Michael L. Lovitz Right Of Publicity And The Intersection Of Copyright And Trademark Law Marc Greenberg Golden Gate University School Of Law, Https://Digitalcommons.Law.Ggu.Edu/Cgi/Viewcontent.Cgi?Article=1485&Context=Pubs

[31] Michael L. Lovitz Right Of Publicity And The Intersection Of Copyright And Trademark Law Marc Greenberg Golden Gate University School Of Law, Https://Digitalcommons.Law.Ggu.Edu/Cgi/Viewcontent.Cgi?Article=1485&Context=Pubs

[32] Defamation Vs. False Light: What Is The Difference? Https://Injury.Findlaw.Com/Torts-And-Personal-Injuries/Defamation-Vs–False-Light–What-Is-The-Difference-.Html

[33] Http://Www.Dmlp.Org/Legal-Guide/False-Light

[34] Twilight: The Fading Of False Light Invasion Of Privacy Andrew Osorio* 174 Nyu Annual Survey Of American Law [Vol. 66:173]

Https://Pdfs.Semanticscholar.Org/449b/F759f23f2118b6f1b216f6dab932e90a8ed0.Pdf

[35] Savare, Matthew, “Image is Everything”, Lowenstein Sandler https://www.lowenstein.com/files/publication/82dfd7a2-5eec-41a0-8412-bd65931a19af/presentation/publicationattachment/f915b2ea-515e-472f-b2e0-be8e7ce33451/publicity%20rights.pdf

[36] Savare, Matthew, “Image is Everything”, Lowenstein Sandler https://www.lowenstein.com/files/publication/82dfd7a2-5eec-41a0-8412-bd65931a19af/presentation/publicationattachment/f915b2ea-515e-472f-b2e0-be8e7ce33451/publicity%20rights.pdf

[37] Revenge Porn Law Could Make It A Federal Crime to Post Explicit Photos Without Permission http://fortune.com/2017/11/28/revenge-porn-law/

[38] https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2162/text

[39] Smith, Brad, 2018, Facial recognition technology: The need for public regulation and corporate responsibility

[40] Judith Donath, July 23, 2018, Medium, https://medium.com/@judithd/you-are-entering-an-ephemeral-bio-allowed-data-capture-zone-5ecafd2dbda

[41] Savare, Matthew, “Image is Everything”, Lowenstein Sandler https://www.lowenstein.com/files/publication/82dfd7a2-5eec-41a0-8412-bd65931a19af/presentation/publicationattachment/f915b2ea-515e-472f-b2e0-be8e7ce33451/publicity%20rights.pdf

1 Response

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hi, this raises really interesting questions about the relationship of national legal systems with international social media terms and conditions.